- Undergraduate

Bachelor's Degrees

Bachelor of ArtsBachelor of EngineeringDual-Degree ProgramUndergraduate AdmissionsUndergraduate Experience

- Graduate

Graduate Experience

- Research

- Entrepreneurship

- Community

- About

-

Search

Transcript

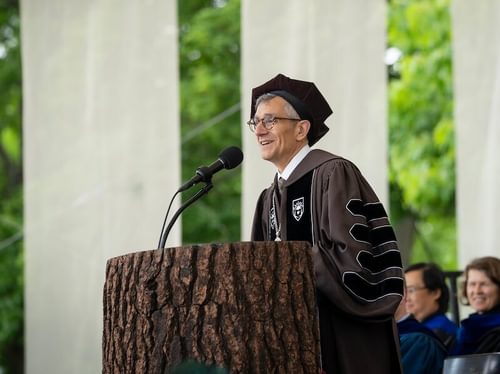

Dean Van Citters, thank you for that kind introduction, I'm truly humbled and honored to receive the Fletcher Award. Through many years of being Dartmouth's engineering dean, I had the privilege of presenting the Thayer award to our Investiture speaker, and not even for a nanosecond did I ever imagine that someday I might find myself as the recipient. Please know how deeply meaningful it is to me to receive this honor.

Thayer and Dartmouth faculty, staff, administrators, students, families and friends, colleagues—it truly is a privilege to be back with you here today on The Dartmouth Green to celebrate this extraordinary class of engineering graduates.

To the students—to the soon-to-be Thayer School of Engineering Dartmouth graduates—congratulations on taking this significant step in this significant journey we call engineering.

I know something about you. Whether you spent much of your time in MacLean or Cummings, Couch or the Great Hall, Murdough or DH, the Machine Shop or Jackson, or the ECSC, I know a little bit of something about where you worked. I also know a little something about how hard you worked. And I know that your family and friends who are here with you today are proud of what you have accomplished, proud—so proud—of seeing you here today crossing this threshold.

I also know that you're coming from a place—this place, Dartmouth and the Thayer School of Engineering—that almost uniquely challenges you to think in terms of intersections:

- the intersection of engineering and the liberal arts

- the intersection of engineering and business management

- the intersection of engineering and medicine, or

- of engineering and entrepreneurship.

It's never 'engineering or' at Dartmouth. It is always 'engineering and.' Now I'm making a point of this because we're experiencing a moment where I believe that 'and'—that connection—is profound. Where that 'and' means nearly everything.

At Lehigh, I speak often of being deeply interdisciplinary, even radically so, and I do that to make that very point—that the 'and' means nearly everything. As Doug said, what we're doing at Lehigh may have borrowed an idea or two that I took away with me from my time here at Dartmouth and the Thayer School of Engineering.

But I'm convinced that those who understand and can operate in the framework of 'and' will be best prepared to navigate this extraordinary moment of change.

You know the change I'm referring to. And I promise you that the provost and I did not plan this and coordinate this in advance, but it is the moment of generative AI.

Text. Code. Images. Increasingly realistic videos. Course syllabi. Lectures. Exams that itself can grade. Powerpoints. Podcasts. Legal memoranda. The list of what it can do, what it can replace, is impressive. And to many, frightening. And this is why academic leaders in almost every setting are making this the focus of their attention.

Just yesterday morning, I was on my campus in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, convening a meeting of six local independent private colleges and universities in the Lehigh Valley, and we spent about ten minutes speaking about our overall strategic planning collectively, sharing resources, things we could do to enhance efficiency and reduce cost on each of our campuses through collaboration. We spent the remaining fifty-plus minutes speaking about generative AI: Opportunity. Questions. Ethics. Impact. And what we can do collectively and collaboratively.

It is everywhere.

A quick google search—or a prompt in ChatGPT or Gemini or your favorite tool—asking about the impact on employment, offers some staggering numbers. By 2030, McKinsey predicts that thirty percent of current work hours in the US will be automated. Thirty percent. One source suggests that up to 11 million workers could be affected in the United States. Another, that 14 million US jobs could be replaced in that same timeframe.

Now, even in the context of a US employment base of 160 million, that number looms large.

And that is just the generative AI piece—throw in biotechnology, robotics, the convergence of physics, chemistry, and biology—and does anyone remember nanotechnology? Top of the news a decade ago. It hasn't gone away—and you have what many are referring to as the convergence or the fourth industrial revolution.

But as an engineer I am a technology optimist. I'm optimistic, and even excited, about the future, and I am optimistic about YOUR future.

Why?

Well, let's take a look at this in the context of other major technology-driven disruptions that we've seen over just the past century. A hundred years ago, the assembly line—Henry Ford's innovation—displaced skilled workers, AND it led to a reduction in the cost of goods and dramatically increased productivity across all sectors. We reinvented ourselves, created something different, and found new opportunity.

A half century ago, from 1960 to 1980s, the computer revolution and particularly the PC—the personal computer—automated data processing, eliminated many clerical and data management jobs, AND led to creation of a whole new 'tech sector' and the birth of new industries. We reinvented ourselves, created something different, and made new opportunity.

Or what about the internet, and then mobile and cloud computing? They transformed entire industries—communications, media, retail transformed. Now, many of your faculty and staff—not you as students—but many of your faculty and staff, perhaps your parents, and yes, even I, are old enough to remember things like telephone booths, printed newspapers delivered to your driveway or front porch in the morning, travel agencies, or hunting for something you needed by physically visiting a broad range of stores without knowing in advance what they might and might not have in inventory. All of that is gone.

But new jobs, new sectors, and new companies emerged. We reinvented ourselves, created something different, and found new opportunity.

Anyone sensing a theme in all of this?

Now, this change doesn't happen overnight, but the arc of a career—the arc of your careers—is long. I'm not worried about the future. And I'm not worried about you. You're smart—clearly smart. We saw that in the awards presentations just a few minutes ago—the extraordinary project work that you've accomplished. And that's important.

You're hard working, and that too is important. I remember back to my time as dean, and whether it was in the MEM space, the Couch Lab, or any of the project spaces, and it sometimes seemed that 11pm or 2am was the most vibrant time of the day. Is that still the case? Only a few nods of recognition—we've gotten soft, apparently, in the past ten years.

You are hard working. Your engineering education—because you are engineers—truly has you prepared, and I am optimistic for your future because each of you embodies that notion of 'engineering and.' Your engineering education teaches you to understand the core of technology, its uses and limits—as Provost Kotz said earlier in his remarks—to be quantitative, to make assumptions, and make informed decisions.

AND, your business education teaches you to understand the allocation of capital, human and financial, necessary for everyone from the Fortune 500 CEOs that some of you will become to the entrepreneurs that many of you will become to the person two weeks from now that you may become trying to manage your very first apartment. That matters.

And your liberal arts education teaches you to understand context, to ask why or why not, to understand history, and community, and culture, and make decisions about technology understanding its relationship to human potential and the human condition.

Putting these together in different ways means you are prepared to ask and answer questions from a range of perspectives. You are not tied to one tool, or one technology, or one way of seeing. You are not intimidated by the potential of generative AI. You know that used well it is an extraordinary tool for human progress and the progress of knowledge.

You've also learned to work collaboratively in teams, and communicate—including with people who are NOT engineers—regardless of your degree program. And I believe that that ability to understand technology, to put it in context, to work together collaboratively, and then most emphatically, to COMMUNICATE is the most important thing that you will take from your education, the most important skill that you have developed here at Dartmouth and Thayer.

Let me tell you a story. A few weeks ago, I was in the Boston area for a day of work-related meetings. After a dinner conversation with an alumnus and former trustee that went late into the evening, I returned to my hotel and got on the elevator to return to my room. Before the doors closed, I was joined by another passenger, a young woman, and I did what I always do, smiled and said 'how are you doing?' as the elevator doors closed.

Now, I do this because that's just who I am. I also do this because, in part, I want to give lie—in case anyone looks at me and sizes me up by the way I'm dressed as an engineer—I want to give lie to the notion that engineers don't communicate, or at least don't communicate with regular people in non-technical language.

Most times a question like this will elicit a simple 'fine, and you?' kind of reply, but that night was different. My fellow passenger looked in my direction, sighed, and said 'How am I? I'm six months pregnant, it's nine-o-clock at night, I'm on a work trip, and I'm carrying a plastic bag filled with takeout from the Cheesecake Factory. I'm living the dream.' I laughed out loud as she stepped off the elevator, thanked her for bringing a little humor to my evening at the end of a long day, and thought about what she said.

'Living the dream.'

That brief conversation's on my mind because I'm often asked these days how I am doing, in a tone that conveys, as some of you may have noticed, the idea that being a university president is perhaps not the most desirable or easiest job in 2025. There are political challenges, on a national level. Financial challenges. The challenges of protecting free speech while at the same time supporting every member of our communities. The challenge of reminding us that the global communities that form the bedrock of the American research university—global communities like the graduates that I see here in front of me, global communities that you have at places like Dartmouth and Lehigh, and MIT and Harvard, and Illinois and Virginia, and every research university in between—thrive and excel precisely because they are global communities.

It's not easy. And yet I truly am living the dream.

Leadership means that we don't get to choose our moment. We don't get to choose the challenges we will face. All we can do is be ready for when that moment comes because, as they say, the moment chooses us.

My engineering education prepared me to think analytically and quantitatively, to break a problem down into its component parts, and to rely on data in making decisions.

My time in the workforce, and particularly my time as a staff member in the United States Senate, and then as the dean of the Thayer School of Engineering and at Dartmouth as provost, helped me learn and practice communicating with a broader audience, and to seeing things from truly a broad range of perspectives. To appreciate the importance of the intersection of engineering and so many other things. And to work hard to always understand the other person's point of view.

I tell you all of this because I know the educational experience that each and every one of you, regardless of program, has had.

You, my friends, are all prepared for these challenges. You have experienced an engineering education and so much more that has given you exposure to all of this. You are prepared to lead. Your education at this extraordinary institution in engineering and so many other things has prepared you, almost uniquely, to navigate the challenges thrown your way. Generative AI. The fourth industrial revolution. Even politics. Or whatever the future may hold. I'm optimistic that you will navigate these moments to create an inclusive and better future for all.

I have the privilege of standing on stages like this, seeing talented students like you, and knowing that we are sending you off fully prepared. In your case—as our student speaker said at the outset—fully prepared to take on 'the most responsible positions and the most difficult service.'

YOU are ready.

And I am so proud to see where you will head. I so look forward to see where you will head and what you will do as you leave this extraordinary institution.

Congratulations, Dartmouth Engineering Class of 2025! Go out and do great things!